|

|

| Korean J Ophthalmol > Volume 24(4); 2010 > Article |

Abstract

A 44-year-old woman with Castleman disease presented with acute visual loss in the left eye. A full ophthalmologic examination and imaging were performed. Visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/100 in the left eye. Total dyschromatopsia, a relative afferent pupillary defect, and a cecocentral scotoma were observed in the left eye. Mild disc edema, without leaking during fluorescein angiography, was also observed. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a small cystic epidermoid-like lesion in the right prepontine and suprasellar cistern. Her visual acuity did not improve and deteriorated to 20/200 in the left eye at 22 months after the initial visual loss. Optic neuropathy may rarely be associated with Castleman disease and suggests a poor prognosis.

Castleman disease (CD) was first described by Dr. Benjamin Castleman and is a rare lymphoproliferative disorder of unknown etiology with different clinical manifestations such as fever, night sweats, malaise, and weight loss [1]. CD is classified into a hyaline vascular variant and plasma cell variant (unicentric and multicentric) [2]. Although several nonlymphoid organs can be involved, ocular findings are very rare. Only cases of serous retinal detachment, thickening of the sclera, involvement of the lacrimal glands, and papilledema associated with an intracranial leptomeningeal mass have been reported [3,4]. An association with optic neuropathy has not been reported to date.

A 44-year-old woman presented with a 3 day history of acute visual loss in the left eye. She did not complain of ocular pain, but she did report a headache localized to the left side beginning one week prior. Two years prior she had suffered from multicentric CD confirmed by histopathologic examination of a cervical lymph node. Rituximab was administered and chemotherapy was performed with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and prednisone. She did not have any other medical history including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, tuberculosis, or hyperlipidemia. She had never smoked and rarely drank alcohol. She had been suffering from myalgia and neuropathy at the onset of the optic neuropathy.

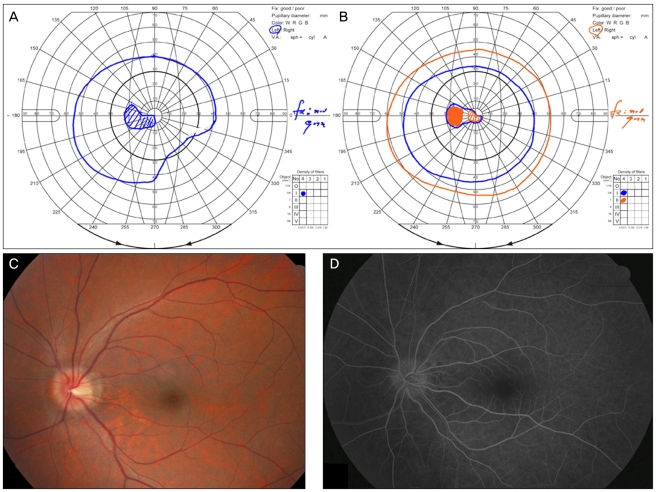

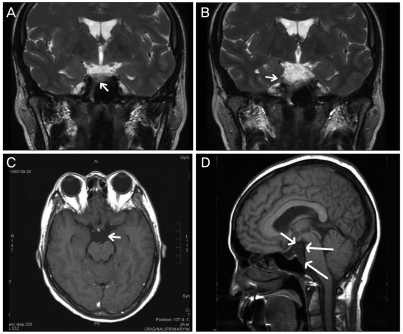

Ophthalmologic examination revealed a best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 20/20 in the right eye and 20/100 in the left eye. A relative afferent pupillary defect was detected in the left eye. Color testing revealed total dyschromatopsia in the left eye. A cecocentral scotoma and inferonasal visual field defect was identified in the left eye (Fig. 1A). Mild disc edema was observed and fluorescein angiography showed mild disc edema without leakage; disc filling time was not delayed (Fig. 1C and 1D). Pattern visual evoked potentials showed a decreased amplitude and delayed latency in the left eye. The mutation for Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy was not detected. Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed a small cystic lesion in the right prepontine and suprasellar cistern, which was suspicious for epidermoid (Fig. 2). The cystic lesion was not associated with the visual pathway, including the optic nerve.

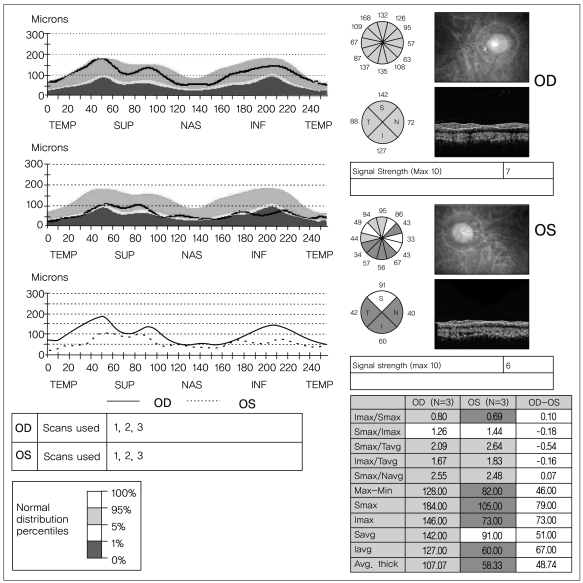

The patient refused to undergo steroid pulse therapy because she had experienced increased blood glucose levels and generalized edema during previous steroid pulse therapy for CD. Two weeks later her BCVA had decreased to hand motion and her visual field demonstrated a superotemporal field defect with a cecocentral scotoma. One month later her BCVA had improved to 20/100 and her color vision had improved to 2 out of 14 plates in the Ishihara color test. The visual field defect also improved to reveal only a central scotoma (Fig. 1B). At final follow-up 22 months later, her BCVA was stable at 20/200 and retinal nerve fiber loss was observed in 4 quadrants in the left eye with Stratus optical coherence tomography (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA) (Fig. 3).

The patient presented herein was slightly younger than the ordinary age for anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION), had no AION risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, or hyperlipidemia, and had no disc hemorrhage. However, she did demonstrate a cecocentral scotoma and total dyschromatopsia. In addition, disc filling time was not delayed during fluorescein angiography. Therefore, this case may be more compatible with optic neuritis compared to AION. The patient did not meet diagnostic criteria for peripheral neuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, a monoclonal plasma cell disorder, and skin changes syndrome because she did not demonstrate monoclonality on repetitive urine protein electrophoresis.

The mechanism behind the association of CD with optic neuropathy is unclear. CD is related to the overproduction of interleukin-6 and hyper-responsiveness to interleukin-6, which is often significantly increased in the serum of patients with optic neuritis [5-7]. Profound immunodeficiency in multicentric CD resulting from apoptosis of T-cells or immunosuppression caused by chemotherapy or the long-term use of steroids may also cause an increased frequency of infection [8]. Finally, we might speculate that the association between multicentric CD and the infection of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpes virus may be relevant to the development of a neuropathy [9]. Altered immunity may be responsible for the development of neuromyelitis optica and CD [10].

In the present case, the patient's final visual acuity was very poor at 20/200. This is in contrast to the usual good visual outcome of optic neuritis [11]. It is not clear whether a more aggressive treatment, such as steroid pulse therapy, would have improved the visual outcome in this case. Our case is the first report to suggest an association of CD with optic neuropathy; further cases can hopefully be identified and used to clarify this association.

REFERENCES

1. Waterston A, Bower M. Fifty years of multicentric Castleman's disease. Acta Oncol 2004;43:698-704.

2. Casper C. The aetiology and management of Castleman disease at 50 years: translating pathophysiology to patient care. Br J Haematol 2005;129:3-17.

3. Kepes JJ, Chen WY, Connors MH, et al. "Chordoid" meningeal tumors in young individuals with peritumoral lymphoplasmacellular infiltrates causing systemic manifestations of the Castleman syndrome: a report of seven cases. Cancer 1988;62:391-406.

4. Severson GS, Harrington DS, Weisenburger DD, et al. Castleman's disease of the leptomeninges: report of three cases. J Neurosurg 1988;69:283-286.

5. Beck JT, Hsu SM, Wijdenes J, et al. Brief report: alleviation of systemic manifestations of Castleman's disease by monoclonal anti-interleukin-6 antibody. N Engl J Med 1994;330:602-605.

6. Ishiyama T, Koike M, Nakamura S, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor expression in the peripheral B cells of patients with multicentric Castleman's disease. Ann Hematol 1996;73:179-182.

7. Deckert-Schluter M, Schluter D, Schwendemann G. Evaluation of IL-2, sIL2R, IL-6, TNF-alpha, and IL-1 beta levels in serum and CSF of patients with optic neuritis. J Neurol Sci 1992;113:50-54.

8. Ishiyama T, Koike M, Fukuchi K, et al. Apoptosis of T cells in multicentric Castleman's disease. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1996;79:271-277.

9. Zumo L, Grewal RP. Castleman's disease-associated neuropathy: no evidence of human herpesvirus type 8 infection. J Neurol Sci 2002;195:47-50.

Fig.┬Ā1

(A) Goldmann visual field examination showed a cecocentral scotoma and inferonasal visual field defect one day after the onset of visual loss. (B) The visual field defect improved to a central scotoma 40 days after the onset of visual loss. (C) Mild disc swelling was observed on fundus photography. (D) Fluorescein angiography demonstrated mild disc edema without leakage.

Fig.┬Ā2

Magnetic resonance imaging revealed an epidermoid-like mass in the right prepontine and suprasella cistern (arrow). (A,B) T2-weighted images. (C) Gadolinium enhanced T2-weighted image. (D) T1-weighted sagittal image.

Fig.┬Ā3

Twenty-two months later, optical coherence tomography showed a diffuse decrease in retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in the left eye. TEMP=temporal; SUP=superior; NAS=nasal; INF=inferior; Imax=inferior maximum; Smax=superior maximum; Navg=nasal average; Savg=superior average; Tavg=temporal average; Iavg=inferior average.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print