Neovascularization of the retina and iris and resultant neovascular glaucoma is a common consequence of chronic retinal ischemic diseases. The new vessels grow at the pupillary border and iris surface (neovascularization of the iris, NVI) and over the iris angle (neovascularization of the angle, NVA). These NVI and NVA form fibrovascular membranes, which progressively obstruct the trabecular meshwork. As the disease progresses, the fibrovascular membranes mature and contract, and pull the iris toward the trabecular meshwork. These processes generate peripheral anterior synechiae and progressive synechial angle closure and cause secondary angle-closure glaucoma or neovascular glaucoma (NVG) [

1].

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy, central retinal vein occlusion, central retinal artery occlusion, and ocular ischemic syndrome can cause neovascularization of intraocular structures as well as NVG. However, the development of ocular neovascularization as a complication of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) has rarely been reported [

2,

3]. There have been a few reports of fluorescein angiography of RRD showing capillary nonperfusion in the detached retinal area [

2,

4-

6]. Vitreous vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) levels in eyes with RD have been reported to be significantly higher than in samples from control patients [

7]. In this retrospective case series, we present 10 eyes from 10 patients with NVG, who had no NVG-predisposing factors other than long-standing RRD.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective study that included patients who visited Seoul National University Bundang Hospital between 2007 and 2016. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (No. B-2112-725-105) and followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for written informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board as the study involved minimal to no risk to the participants.

Patients were included if they had a history of chronic retinal detachment and NVI or NVG. The diagnosis of a chronic RRD is generally based on clinical findings and patient history. Chronic RRD in the present study was defined as a history of definite vision loss or visual field defect for ≥3 months with the following corresponding clinical findings: pigmented demarcation line, white proliferative strand, retinal thinning, or intraretinal crystalline opacities [

8-

10]. Patients who had predisposing conditions for intraocular neovascularization, such as carotid artery disease, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, retinal vein occlusion, or ocular ischemic syndrome, were excluded.

A total of 10 eyes of 10 patients were included in the study. Data on medical history and clinical features, including visual acuity (VA), intraocular pressure (IOP), slit-lamp examination, fundus examination, fundus fluorescein angiography, and treatment methods were obtained. As some patients were unable to recall the exact time of RD onset, the data were approximated according to the patient’s memory.

Results

There were five male patients and five female patients. The mean age of all patients was 57.5 years (range, 22-78 years). All patients had unilateral NVG, with the involvement of three right and seven left eyes. No patients had diabetes, and four patients had hypertension, which was well-controlled by medication. No patients had evidence of any systemic disease accounting for the retinal neovascularization, such as carotid artery stenosis, or a family history of vascular diseases (

Table 1).

The ophthalmologic features of the patients are presented in

Table 2. Initial VA was poor in all patients. There was no light perception in three patients (cases 1, 2, and 6), light perception only in two patients (cases 5 and 9), hand motion in three patients (cases 3, 7, and 8), VA of 20/400 in one patient (case 4), and of 20/1,000 in one patient (case 10), based on the Snellen visual acuity chart. RD was diagnosed at year 1991 in one patient (case 6), 2002 in one patient (case 7), 2007 in three patients (case 3, 8, and 9), and 2011 in two patients (cases 4 and 10). Three patients did not have a history of vitreoretinal surgery; six patients had pars plana vitrectomy, and three patients underwent scleral buckling for RD. Seven patients received combined therapy for NVG and RRD.

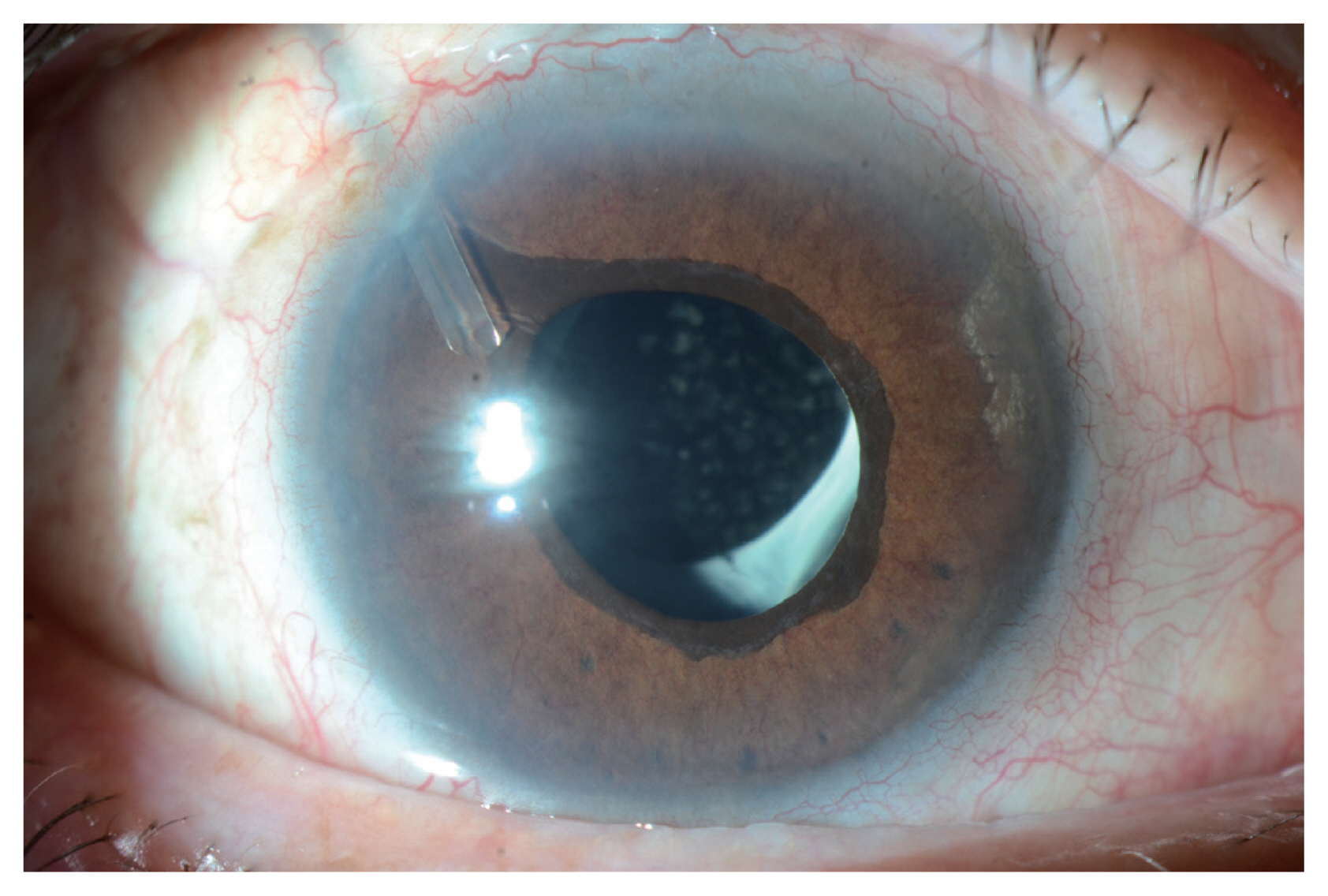

Five patients had NVI and had high IOP at the initial presentation (

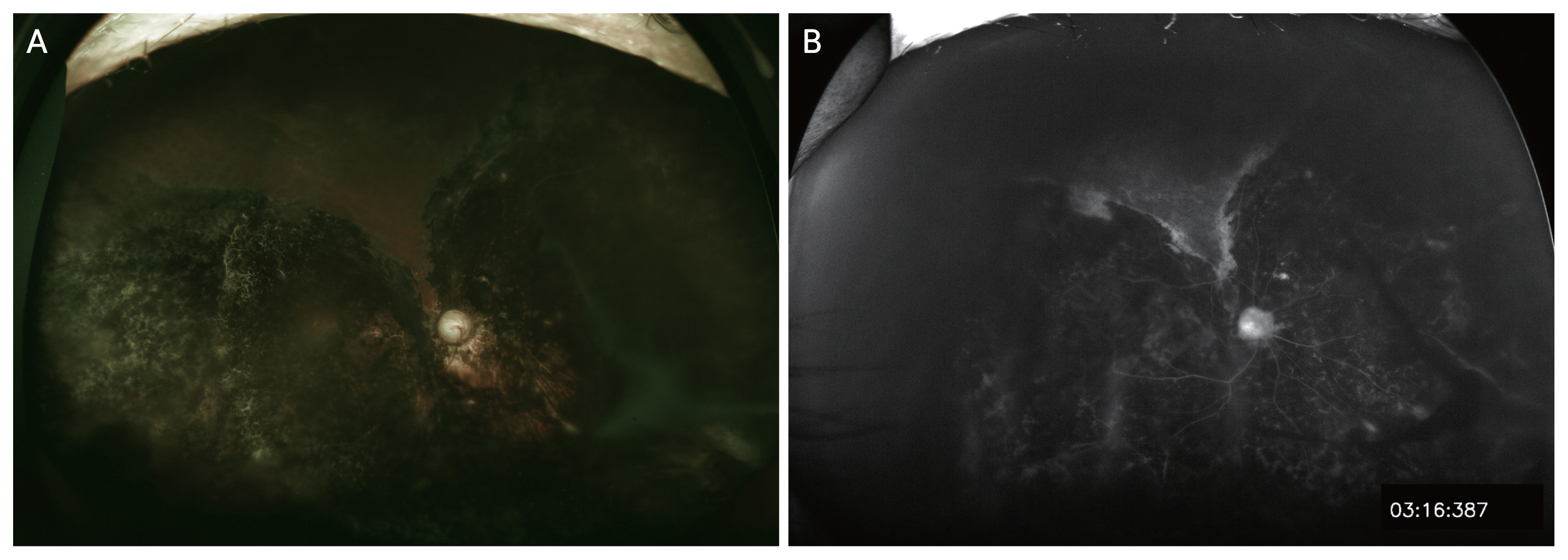

Fig. 1). During follow-up, NVI as well as IOP elevation were observed in all patients. All patients were diagnosed as having NVG. The mean time from onset of RRD to the onset of NVI or NVG was 213.4 months (range, 17-634 months). In three patients, NVG occurred even after achieving reattachment of the detached retina (

Fig. 2A, 2B,

3A-3C). Ultra-wide field fluorescein angiography was performed in two cases (cases 1 and 8), both of which showed wide areas of retinal capillary obstruction as well as retinal vascular leakage in the reattached retina. Interestingly, the retinal capillary obstruction was also present in the nondetached retina.

To control high IOP, Ahmed valve implantation was performed in three eyes, and intravitreal bevacizumab injection was performed in five eyes. All patients used topical IOP lowering medications. Prophylactic scatter laser photocoagulation was performed in one eye (case 1), because of the wide retinal nonperfusion seen on fluorescein angiography. IOPs were controlled in 10 of 10 eyes. However, two eyes (cases 5 and 7) developed phthisis bulbi during follow-up.

Discussion

Our study showed that NVG can develop in eyes with chronic RD, even in the absence of predisposing conditions, such as carotid artery diseases. Additionally, none of the patients underwent encircling scleral buckle surgery and had inflammatory findings during follow-up, which could have been associated with peripheral retinal ischemia.

Rarely, RD can cause NVI and NVG [

11-

13]. A previous study has reported that NVI is associated with chronic RD [

12]. They revealed that risk factors for NVI are an age ≥50 years, severe myopia, a history of increased IOP, a history of choroidal detachment, and a large scleral buckle. In that study, six of 30 patients showed improvement of NVI after reattachment. Another study revealed that new retinal vessels were totally regressed within 15 days to 3 months after retinal reattachment, in nine of nine eyes [

11]. However, our cases showed persistent NVI and experienced NVG even after successful retinal reattachment.

In the present study, only three of 10 patients had proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR), none of whom had anterior PVR. Considering that seven patients developed NVI or NVG even without PVR and that PVR rarely improves spontaneously, but NVI sometimes regresses spontaneously when the retina reattaches [

14], the relationship between PVR and NVG in our cases seems low.

The pathogenic mechanism underlying development of NVI and NVG most likely involves retinal capillary obstruction and retinal ischemia, as shown by ultra-wide field fluorescein angiography in our cases. However, it is unclear why retinal capillary obstruction occurs even in the attached retina. Postoperative inflammation and retinal vasculitis may be the cause of retinal vascular obstruction, but this should be further investigated. In previous studies, it was considered that the new peripheral retinal vessels formed secondary to retinal hypoxia due to reduced retinal blood flow in the detached retina. Persistent RD and reduction in choroidal and retinal circulation was thought to play roles in ocular neovascularization [

11,

12]. In addition, as posterior vitreous detachment usually occurred in eyes with RD, neovascularization would develop in the anterior segment, rather than in the posterior segment, resulting in NVG.

It is noteworthy that NVG occurred even after achieving reattachment of a detached retina in our cases. Fluorescein angiography showed diffuse widespread nonperfusion areas and leakage in the reattached retina. Therefore, regular follow-up examinations, including careful inspection of the NVI, as well as NVA are recommended for patients who have a history of chronic RD. In cases that failed to achieve retinal reattachment, even more caution should be taken, and patients should be informed of the possibility of developing NVG.

Our study has several limitations. First, an insufficient number of patients and their clinical data were included in this study. Nevertheless, ultra-wide field fluorescein angiography revealed widespread areas of nonperfusion in both the detached and reattached retina, which support the hypothesis that the retinal capillary nonperfusion and resultant retinal ischemia is likely to be the main pathogenic mechanisms of NVI and NVG. Second, other retinal diseases with similar phenotypes could not be completely excluded. However, on fundus examination of the fellow eyes and the undetached retina in the study eyes, we could not find any evidence of retinal ischemia before the onset of RRD. Considering recent reports that long-standing RD causes peripheral retinal ischemia and the increase in vitreous VEGF levels [

15,

16], we considered it reasonable that the chronic RD itself caused retinal ischemia and subsequent NVG rather than preexisting diseases.

In eyes with a history of chronic RD, NVI and NVG can develop due to peripheral retinal capillary obstruction and retinal ischemia, even after achieving reattachment of the retina. We suggest routine follow-up examinations for patients who have suffered chronic RD, especially in eyes with retinal peripheral nonperfusion on fluorescein angiography.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print