A Case of Acquired Brown Syndrome after Surgical Repair of a Medial Orbital Wall Fracture

Article information

Abstract

A case of acquired Brown syndrome caused by surgical repair of medial orbital wall fracture is reported in the present paper. A 23-year-old man presented at the hospital with right periorbital trauma. Although the patient did not complain of any diplopia, the imaging study revealed a blow-out fracture of the medial orbital wall. Surgical repair with a calvarial bone autograft was performed at the department of plastic surgery. The patient was referred to the ophthalmologic department due to diplopia that newly developed after surgery. The prism cover test at distant fixation showed hypotropia of the right eye, which was 4 prism diopters (PD) in primary gaze, 20 PD in left gaze, while orthophoric in right gaze. Eye movement of the right eye was markedly limited on elevation in adduction with normal elevation in abduction with intorsion in the right eye present. Forced duction test of the right eye showed restricted elevation in adduction. Computerized tomography scan of the orbits showed the right superior oblique muscle was entrapped between the autografted bone fragment and posterior margin of the fracture. When repairing medial orbital wall fracture that causes Brown syndrome, surgeons should always be careful of entrapment of the superior oblique muscle if the implant is inserted without identifying the superior and posterior margin of the orbital fracture site.

Brown syndrome is characterized by impaired elevation in the adduction of the affected eye. Forced duction test shows severe mechanical restriction on attempts to elevate the adducted eye with no limitations of elevation in abduction [1]. A widening of the palpebral fissure is commonly seen with adduction. Overaction of the ipsilateral superior oblique muscle is usually absent in Brown syndrome. Brown syndrome can be either congenital or acquired [2]. The cause of congenital Brown syndrome is an anomaly of the trochlea and/or superior oblique tendon. Inflammatory diseases, infection, systemic disease and trauma can cause acquired Brown syndrome [3].

Many of the surgical procedures, such as scleral buckling, glaucoma drainage implantation, ethmoidal sinus surgery and tucking the superior oblique tendon can lead to acquired Brown syndrome [4-6]. There are several reports of postoperative Brown syndrome after surgery for orbital wall fracture [7, 8]. However, to the authors' knowledge, acquired Brown syndrome caused by superior oblique muscle entrapment between the implant and posterior margin of the fracture has not been documented, thus the authors report a case of acquired Brown syndrome as well as a review of related literature in the present paper.

Case Report

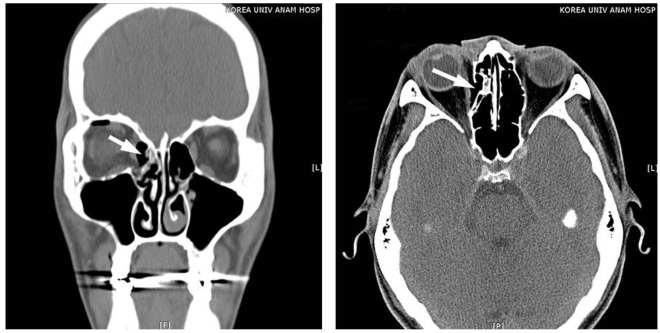

A 23-year-old man presented to the hospital with right periorbital injury caused by blunt trauma. When the patient first visited our institution, ophthalmologic evaluation including visual acuity, slit lamp examination, intraocular pressure, and fundus examination revealed no abnormal findings. The patient was orthophoric in all gaze positions on the alternate prism cover test, no limitation was observed on version and duction test, and the patient did not complain of diplopia. Computerized tomography scan of the orbits showed a medial wall fracture (Fig. 1). Surgical repair of the fracture using a calvarial bone autograft was performed at the department of plastic surgery 3 days after the injury (Fig. 2). Immediately after surgery, the patient complained of newly-developed diplopia. The patient visited the ophthalmologic department 2 months after the surgery.

A computerized tomography scan was performed before surgery and showed a medial orbital wall fracture (arrow).

Postoperative computerized tomography scan of the orbits showed the right superior oblique muscle was entrapped between the autografted bone fragment and posterior margin of the fracture (arrow).

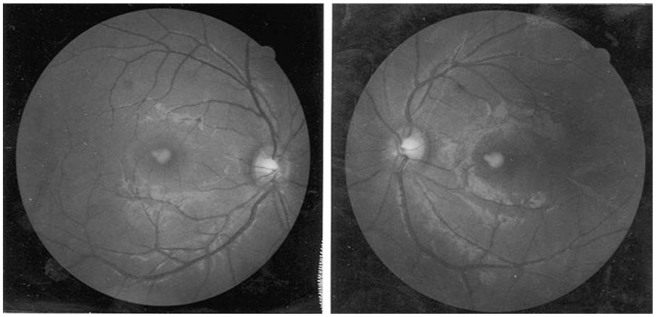

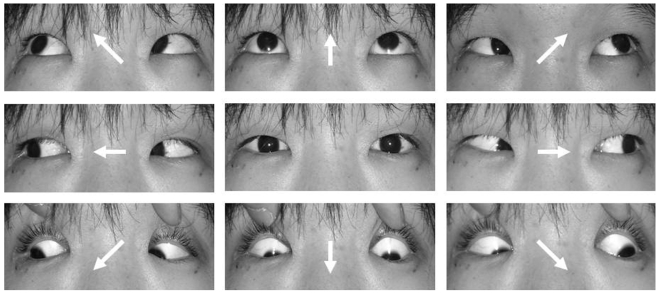

A prism cover test at distance fixation revealed 4 prism diopters (PD) of right hypotropia in the primary position, 20 PD hypotropia in left gaze, and orthophoric in right gaze. Eye movement of the right eye was markedly limited on elevation in adduction while elevation in abduction was normal (Fig. 3). Fundus examination showed intorsion of the right eye (Fig. 4). Forced duction test of the right eye demonstrated restricted elevation in adduction. A postoperative CT scan of the orbits showed the right superior oblique muscle was entrapped between the autografted bone fragment and posterior margin of the fracture (Fig. 2).

After repair of the blow-out fracture, limitation of elevation in adduction of the right eye developed (arrow) while elevation in abduction was normal.

Discussion

Parks and Brown [1] first reported on an unusual motility disorder characterized by limited elevation when the eye is in adduction. At first, Brown attributed the limited elevation to a short or tight anterior superior oblique tendon sheath and termed this newly discovered syndrome the "superior oblique tendon sheath syndrome". Later, Brown divided the syndrome into true sheath and simulated sheath syndromes based on whether the congenital short anterior sheath of the superior oblique tendon is the only cause of the symptom or not [9]. The clinical features of true and simulated sheath syndromes are similar, but true sheath syndrome is always congenital as well as constant, and does not show spontaneous recovery. The true sheath syndrome was further subdivided into typical and atypical forms [10].

A classification of Brown's syndrome can be made on the basis of onset, and congenital versus acquired. Acquired Brown syndrome is associated with limited elevation in adduction that occurs after infancy. In certain cases, acquired Brown syndrome is idiopathic. In other instances, Brown syndrome can be associated with a systemic disease or local orbital pathology [2].

Inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus, can cause acquired Brown syndrome [11-14]. Local inflammation of the superior oblique tendon and trochlea can occur as an idiopathic form without systemic disease [15, 16]. Scarring in the area of the trochlea from trauma or from periocular or sinus surgery can also produce Brown syndrome [17, 18].

There are numerous case reports of postoperative Brown syndrome. Dobler et al. [19] reported Brown syndrome after implantation of a double plate Molteno valve in the superior nasal position. Coats et al. [6] reported Brown syndrome after Ahmed valve® implantation. Ball et al. [4] reported a case of Brown syndrome after Baevelt implantation. Munoz and Rosenbaum [5] observed Brown syndrome after retinal detachment surgery.

Brown syndrome related to surgical repair of an orbital wall fracture has also been reported. Lauer et al. reported Brown syndrome diagnosed following repair of an orbital roof fracture [7]. Hwang and Lim [20] reported Brown syndrome after reconstruction of a medial wall fracture and observed the tendon and muscle fiber near the trochlea were hypertrophied. Surgical or accidental trauma to the area of the trochlea has been reported to cause acquired Brown syndrome. In medial orbital wall reconstruction surgery, the superior oblique muscle is easily damaged because of its close proximity. The superior oblique muscle and the tendon can be injured during an operation, or adhesion can occur post-operatively. Edema or hemorrhage can also induce Brown syndrome [21].

In the present case study reported, the authors could confirm by CT scan of the orbits that the right superior oblique muscle was entrapped between the autograft bone fragment and posterior margin of the fracture (Fig. 2).

The indications for Brown syndrome surgery include hypotropia in the primary position, diplopia, anomalous head posture, and downshoot during adduction [22]. There are several surgical procedures for the treatment of Brown's syndrome including superior oblique tenotomy, tenectomy and elongation of the superior oblique muscle [23].

In the present case study, removal of the bone graft was difficult, and even if successfully performed, the symptoms due to adhesion probably would not improve. As hypotropia at the primary gaze was small and the patient did not want surgical management, the authors decided to manage the patient conservatively.

In reconstruction of medial wall blow-out fracture, there is a risk of external ocular muscle entrapment. The muscle entrapment can occur when the implant is inserted without identifying the margin of fracture clearly. Although superior oblique entrapment is not common, the surgeon should always consider the possibility of Brown syndrome if the implant is placed without securing the superior and posterior margin of the orbital fracture site, at which the superior oblique may strangulate. Surgeons should also perform an intraoperative forced duction test after inserting the implant to ensure all extraocular muscles are released.

Notes

This paper was presented in part at the 97th annual meeting of the Korean Ophthalmological Society, April. 2007.