Light consists of a wide range of electromagnetic waves, among which UV or blue light with a short wavelength is known to damage the retina. Although the electromagnetic radiation produced by welding equipment depends on the particular technique being used and the voltage, its composition is similar to that of light.

Welding techniques have improved over the years, from coated metal arc welding to the present day use of higher temperature gas tungsten arc welding and gas metal arc welding. Recently, the creation of plasma in atmospheric air has become possible, and numerous researchers are studying its potential applications. Plasma arc welding has a good energy concentration ratio, and its temperature reaches 10,000 to 30,000 degrees Celsius. For this reason, plasma arc welding has reduced the duration of welding operations. As a result, it has become the preferred welding technique. However, the high temperature of plasma arc welding results in the radiation of many electromagnetic waves, making it more likely to cause retinal damage than conventional arc welding techniques.

Photic retinal injury caused by welding is quite rare. The first case was reported in 1902, when Terrien studied subway construction workers. However, until now, no cases of photic retinal injury associated with plasma arc welding have been published in the literature. In addition, there have been no reports of OCT being used to examine a retinal lesion associated with photic retinal injury. Herein we report on a case of photic retinopathy induced by plasma arc welding which was investigated using OCT, along with a review of the associated literature.

Case Report

A 37-year-old male visited our hospital complaining of acute loss of vision and central scotoma. He was a welder in the steel industry. One day before he visited, he had been using plasma arc welding equipment while wearing protective goggles.

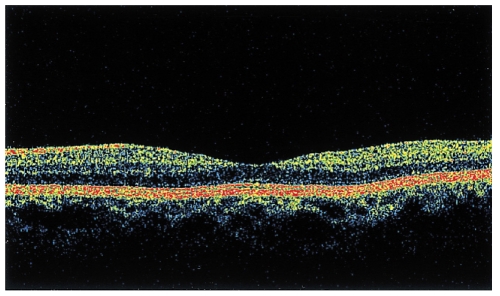

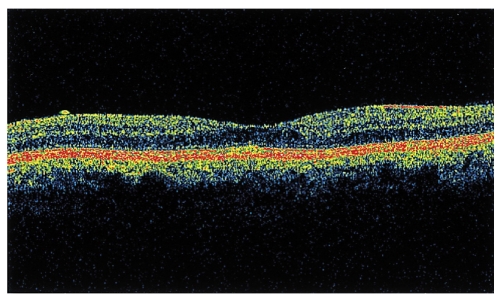

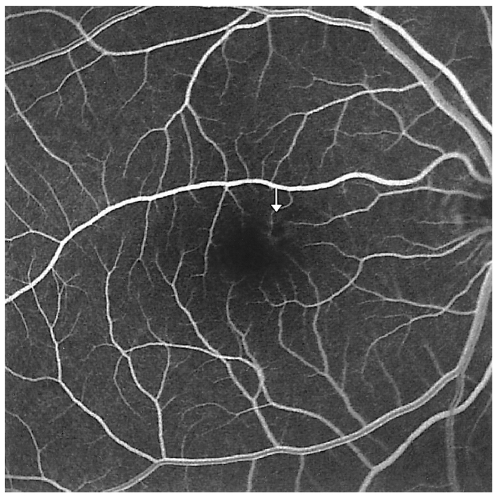

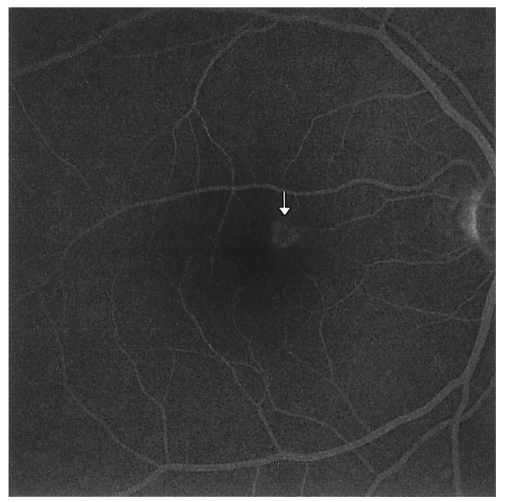

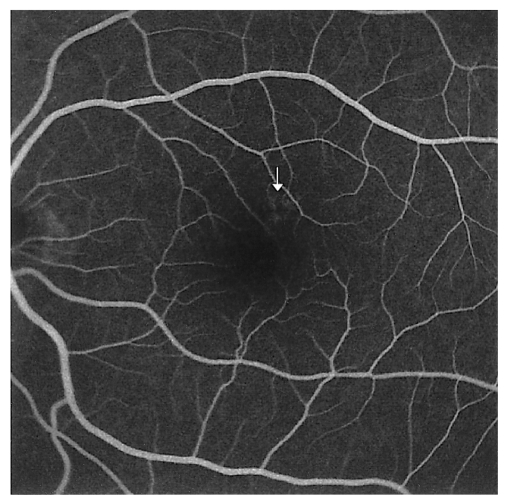

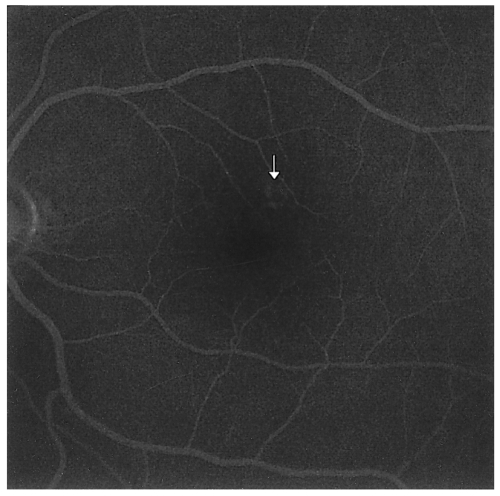

His best corrected vision was tested and was found to be 0.7 for both eyes, and no keratitis was observed. Fundus examination revealed the presence of a round yellow lesion about 300 micrometers in size superonasal to the fovea of both eyes (Fig. 1). Although the visual field test did not reveal any apparent signs of central scotoma, scotoma was observed in the central region using the Amsler grid test (Fig. 2). The lesion of the macula was scanned using OCT, and no abnormal signs were observed (Fig. 3). H-R-R plates (Hardy-Rand-Rittler plates) were used to test color vision and no abnormal signs were observed. On the same day, the patient was examined with fluorescein fundus angiography. In the early phase, ring-shaped paracentral hyperfluorescence appeared simultaneously with a central dark halo. In the late phase, the dark center of the lesion was surrounded by progressively increasing hyperfluorescence (Figs. 4, 5, 6, and 7).

He was put under observation without any specific treatment for a month. After a month of follow-up studies, his best corrected vision improved to 1.0 and the central scotoma disappeared. The lesion in the macula was no longer visible.

Discussion

Welding-induced photic retinal injury is clinically rare and was first reported by Terrien in 1902. The high temperature light waves that are radiated while welding emit wide ranges of electromagnetic waves. UV, near ultraviolet ray, and blue light, all part of the wider ranging light spectrum, can damage the eyes. Welders are also susceptible to an increase in their body temperature due to the environment in which they work. Furthermore, since wearing protective masks reduces their field of vision, many welders frequently prefer not to use them for simple welding.

The most frequent ocular damage from welding is photokeratitis. It takes about 6 to 12 hours for the symptoms to occur after the exposure to light radiation during welding. Molecules such as interleukins, cytokines, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) take part in this inflammatory response.1 Although many patients initially complain of pain, glaring, and tears, many of these symptoms fade away after 36 to 72 hours.

The advances made in welding techniques have resulted in the increasing use of plasma arc welding and laser welding. Plasma is a highly ionized gas that can conduct electrical current. Matter exists in three phases, solid, liquid, and gas. When enough energy is given to gaseous matter, the temperature of the gas increases dramatically. When more energy is supplied, gas molecules are disintegrated into their component atoms, atomic structure breaks down, and atoms lose their electrons. Thus, this phase of matter, consists of protons and free electrons. This phase is said to be the fourth phase of matter, or the plasma phase. Plasma arc welding generates a high temperature range of 10,000 to 30,000 degrees Celsius, and can radiate more harmful light beams to the human body that can cause more eye-associated complications than conventional arc welding techniques.

Protective goggles containing appropriate lenses are essential. Oliver Arend reported a case of a 26-year-old male with eyes damaged with welding-induced photic retinal injury, even though he wore protective goggles at work. Examination of the lenses in the goggles revealed that they could only absorb light waves with a wavelength less than 380 nm, and could only afford protection against photokeratitis.2 In our case, the patient also wore protective goggles. Although he did not develop complications of the anterior segment such as photokeratitis, he developed and suffered from photic retinal injury.

It is known that the findings of fluororescein fundus angiography are usually normal, but a slight defect and aggregation of the retinal pigment epithelium can be observed.3 In our case, ring-shaped paracentral hyperfluorescence appeared simultaneously with a central halo. We suspect it was caused by the partial loss and aggregation of the retinal pigment epithelium. The result of the OCT examination showed no specific signs. In the case of photic retinal injury, histopathologically, the outer segment of photoreceptor is the main area of damage.4,5 We believe the extent of the tissue damage was insufficient to be observed by OCT in this case.

Although the prognosis of welding-induced photic retinal injury is usually good,6-8 permanent complications are sometimes reported.2 Oral steroid treatment for photic retinal injury has been reported, but its effect was unclear. Shahriari et al. suggested that taking vitamin A and aspirin can reduce the risk of developing photic retinal injury.9 Welders must be educated about photic retinal injury and the need to wear proper protective goggles to avoid potential damage to their eyes caused by the vast range of harmful light waves.2 In addition, when patients with welding-induced photokeratitis are encountered in the clinic, they should be provided with a full explanation of the possibilities of photic retinal injury.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print