Severe Adverse Events of Periocular Acupuncture: A Review of Cases

Article information

Abstract

Acupuncture is recognized as a component of alternative medicine and is increasingly used worldwide. Many studies have shown the various effects of acupuncture around the eyes for ophthalmologic or nonophthalmologic conditions. For ophthalmologic conditions, the effect of acupuncture on dry eye syndrome, glaucoma, myopia, amblyopia, ophthalmoplegia, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, blepharospasm, and blepharoptosis has been reported. Recently, several studies on dry eye syndrome have been reported and are in the spotlight. However, given the variety of study designs and reported outcomes of periocular acupuncture, research is still inconclusive, and further studies are required. In addition, although a systematic and reliable safety assessment is required, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports of a literature review of ocular complications resulting from periocular acupuncture. This review collected cases of ocular injury as severe adverse events from previously published case reports of periocular acupuncture. A total of 14 case reports (15 eyes of 14 patients) of adverse events published between 1982 and 2020 were identified. This review article provides a summary of the reported cases and suggestions for the prevention and management of better visual function prognosis.

Introduction

Acupuncture is a traditional treatment method developed in East Asia over a significant period of time and is now recognized as an important component of complementary and alternative medicine worldwide [1–3].

In the field of ophthalmology, papers have been published on the effectiveness of acupuncture for some ophthalmologic diseases, and meta-analysis of diseases, such as dry eye syndrome, glaucoma, slowing myopia progression, amblyopia, and acute hordeolum, have been published or are in progress [2–8]. Recently, several studies, including meta-analysis, regarding dry eye syndrome have been reported and are in the spotlight [4,5,9]. However, adverse events, such as penetrating injuries caused by acupuncture around the eyes, have been reported constantly [10–22]. These disastrous events are related to the site of acupuncture, which depends on the target disease.

Generally, periocular acupuncture may affect the ocular surface condition as either an effect or a possible side effect. Therefore, the target disease, location of acupuncture, expected benefits, and frequency and severity of serious side effects need to be discussed together. In this article, we reviewed the literature of previously reported ocular penetration caused by acupuncture to provide information on the safety of acupuncture treatment around the eye in an organized manner.

Acupuncture points in the periocular area

The World Health Organization (WHO) has made efforts to standardize the terminology of oriental medicine by gathering experts from various countries to facilitate mutual exchange and prevent confusion of terms [1,23]. Since the organization of the working group on the standardization of acupuncture nomenclature in 1981 by the WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, standard terms for the names of acupuncture points have been derived and published through the Standard Acupuncture Nomenclature (Second Edition) in 1993 [23] and the WHO Standard Acupuncture Point Locations in the Western Pacific Region in 2008 [24].

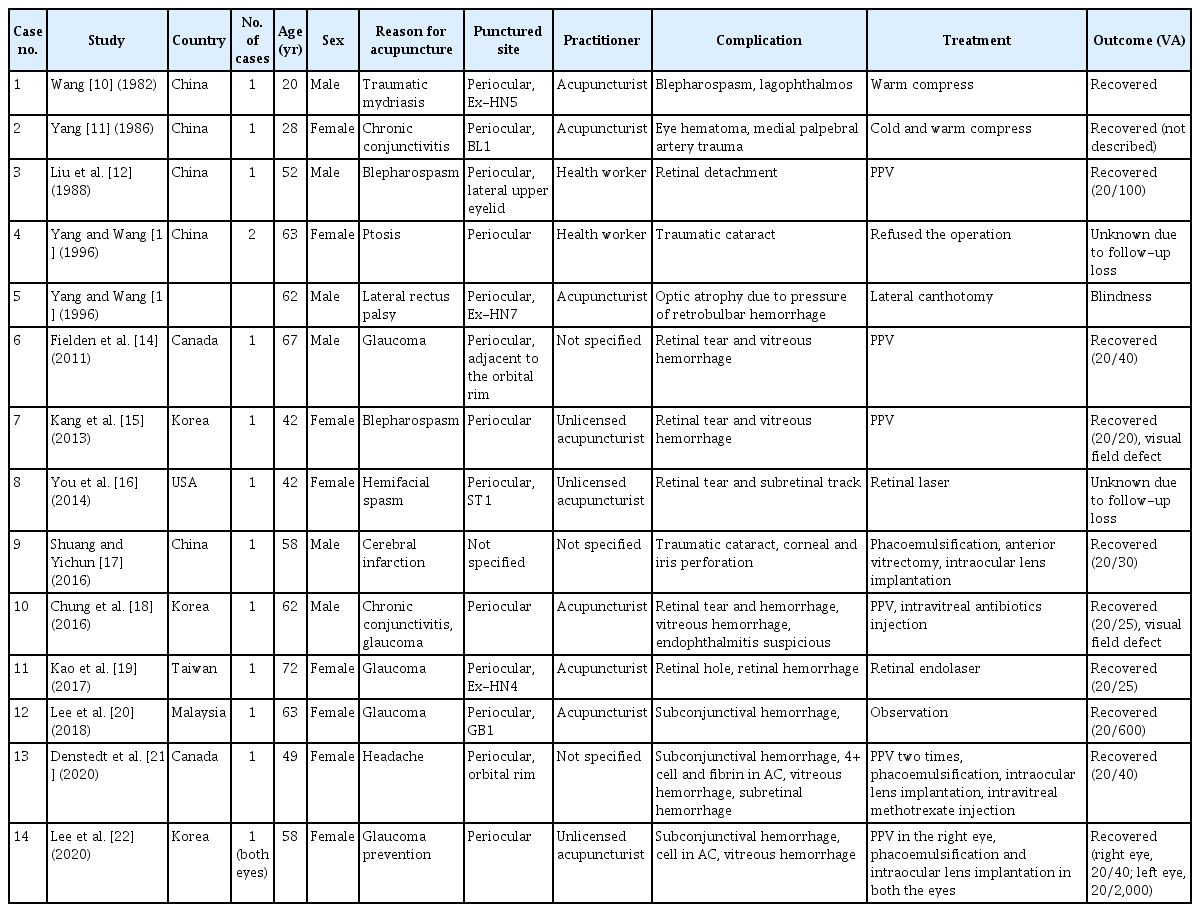

Traditionally, 361 classical acupuncture points were organized according to the 14 meridians: lung (LU1–LU11), large intestine (LI1–LI20), stomach (ST1–ST45), spleen (SP1–SP21), heart (HT1–HT9), small intestine (SI1–SI19), bladder (BL1–BL67), kidney (KI1–KI27), pericardium (PC1–PC9), triple energizer (TE1–TE23), gallbladder (GB1–GB44), liver (LR1–LR14), governor vessel (GV1–GV28), and conception vessel (CV1–CV24) [24]. Of the 361 classical acupuncture points, only six points were located in the periorbital area, including BL1 (jingming) and BL2 (cuanzhu) in the bladder, GB1 (tongziliao) in the gallbladder, ST1 (chengqi) and ST2 (sibai) in the stomach, and TE23 (sizhukong) in the triple energizer meridians. However, four additional acupuncture points in the periorbital area were known as extra points of the head and neck, including Ex-HN3 (yintang), Ex-HN4 (yuyao), Ex-HN5 (taiyang), and Ex-HN7 (qiuhou) (Fig. 1) [25]. The locations of acupuncture points are defined as follows [24,25].

Acupuncture points in the periorbital area. The left side illustrates the classical acupuncture points in the periorbital area, including the six standard points, which are BL1 (jingming), BL2 (cuanzhu), GB1 (tongziliao), ST1 (chengqi), ST2 (sibai), and TE23 (sizhukong). The four extra points of the head and neck are Ex-HN3 (yintang), Ex-HN4 (yuyao), Ex-HN5 (taiyang), and Ex-HN7 (qiuhou). Further, other reported acupuncture points are shangming, neitongziliao, and jianming. The right side illustrates the thirteen acupuncture points of the eye, namely, lung, large intestine, kidney, bladder, upper jiao, liver, gallbladder, middle jiao, heart, small intestine, spleen, stomach, and lower jiao bladder, extra points of head and neck, gallbladder, stomach, triple energizer. Illustration by Chehyun Lee.

1) BL1 (jingming)

BL1 is located on the face, in the depression between the superomedial parts of the inner canthus of the eye and medial wall of the orbit, 0.1 cun (a traditional Chinese unit of length, 1 cun = 3⅓cm) superior to the inner canthus when the eye is closed. The needle is perpendicularly inserted 0.3–0.7 cun into the skin.

2) BL2 (cuanzhu)

BL2 is located on the head, in the depression at the medial end of the eyebrow. A depression, the frontal notch, can often be palpated on the medial end of the eyebrow directly superior to BL1. The needle is subcutaneously inserted 0.3–0.5 cun into the skin.

3) GB1 (tongziliao)

GB1 is located on the head, in the depression, 0.5 cun lateral to the outer canthus of the eye. The needle is subcutaneously inserted 0.3–0.5 cun into the skin.

4) ST1 (chengqi)

ST1 is located on the face, between the eyeball and infraorbital margin, directly inferior to the pupil. The needle is perpendicularly inserted 0.5–1.0 cun into the skin.

5) ST2 (sibai)

ST2 is located on the face, in the infraorbital foramen, 0.5 cun inferior to ST 1 when eyes are focused forward. The needle is perpendicularly inserted 0.3–0.5 cun into the skin.

6) TE23 (sizhukong)

TE23 is located on the head, in the depression at the lateral end of the eyebrow, TE23 is superior to GB1. The needle is subcutaneously inserted 0.3–0.5 cun into the skin.

7) Ex-HN3 (yintang)

Ex-HN3 is located at the midpoint between the two medial ends of the eyebrows. The needle is horizontally inserted 0.5 cun downwards.

8) Ex-HN4 (yuyao)

Ex-HN4 is located at the midpoint of the eyebrow in a depression directly above the pupil. The needle is horizontally subcutaneously inserted 0.5 cun into the skin.

9) Ex-HN5 (taiyang)

Ex-HN5 is located at the temple, in a depression, approximately 1 cun posterior to the midpoint between the lateral end of the eyebrow and outer canthus of the eye. The needle is perpendicularly inserted 0.5 cun.

10) Ex-HN7 (qiuhou)

Ex-HN7 is located on the face region, at the junction of the lateral one-fourth and medial three-fourths of the infraorbital margin.

Periorbital acupuncture was used not only for ophthalmologic diseases, but also for nonophthalmologic diseases, such as headaches, acute lumbar pain, and lumbar disc herniation, based on the theory of Traditional Chinese Medicine on the relationship among the eyes, brain, viscera, and meridians [26]. Moreover, “eye acupuncture” using the 13 acupuncture points around the eyes have been developed and studied since 1970, and the referred acupoints are the lung, large intestine, kidney, bladder, upper jiao, liver, gallbladder, middle jiao, heart, small intestine, spleen, stomach, and lower jiao (Fig. 1) [26].

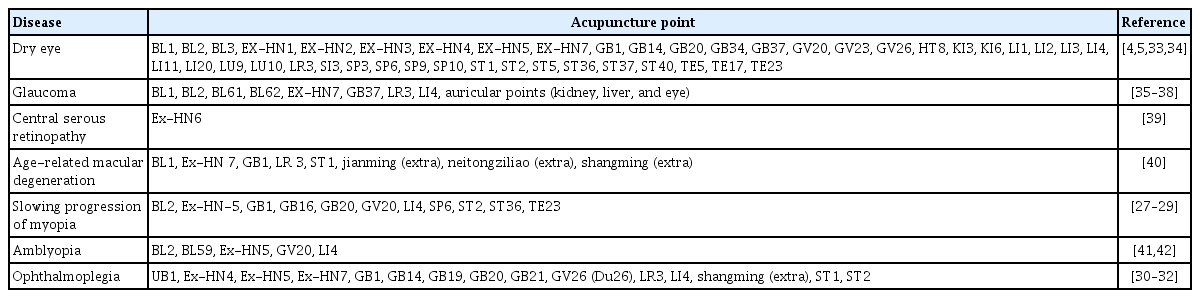

Reported sites of acupuncture for ophthalmologic diseases

Based on the theory of the relationship between the eyes, brain, viscera, and meridians, acupuncture points for ophthalmologic diseases are not limited to the periorbital area. Information on the acupuncture points used in randomized controlled trials for ophthalmologic diseases has been summarized in Table 1 [4,5,27–42]. Most studies used several points, both periorbital and nonperiorbital, and a relatively large variety was observed for the same diseases [2,4,27–32].

Review of Cases with Adverse Events of Periocular Acupuncture

Search strategy

We searched four databases in an attempt to locate any and all existing English-language case reports on adverse events of acupuncture published between 1980 and 2020. The following databases were searched: PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, and KoreaMed. Search terms included acupuncture, acupuncture points, and needling. These terms were combined with safety, adverse event, injury, adverse reaction, side effects, complications, and risk. We then screened the literature reporting adverse events related to ocular damage.

Summary of cases

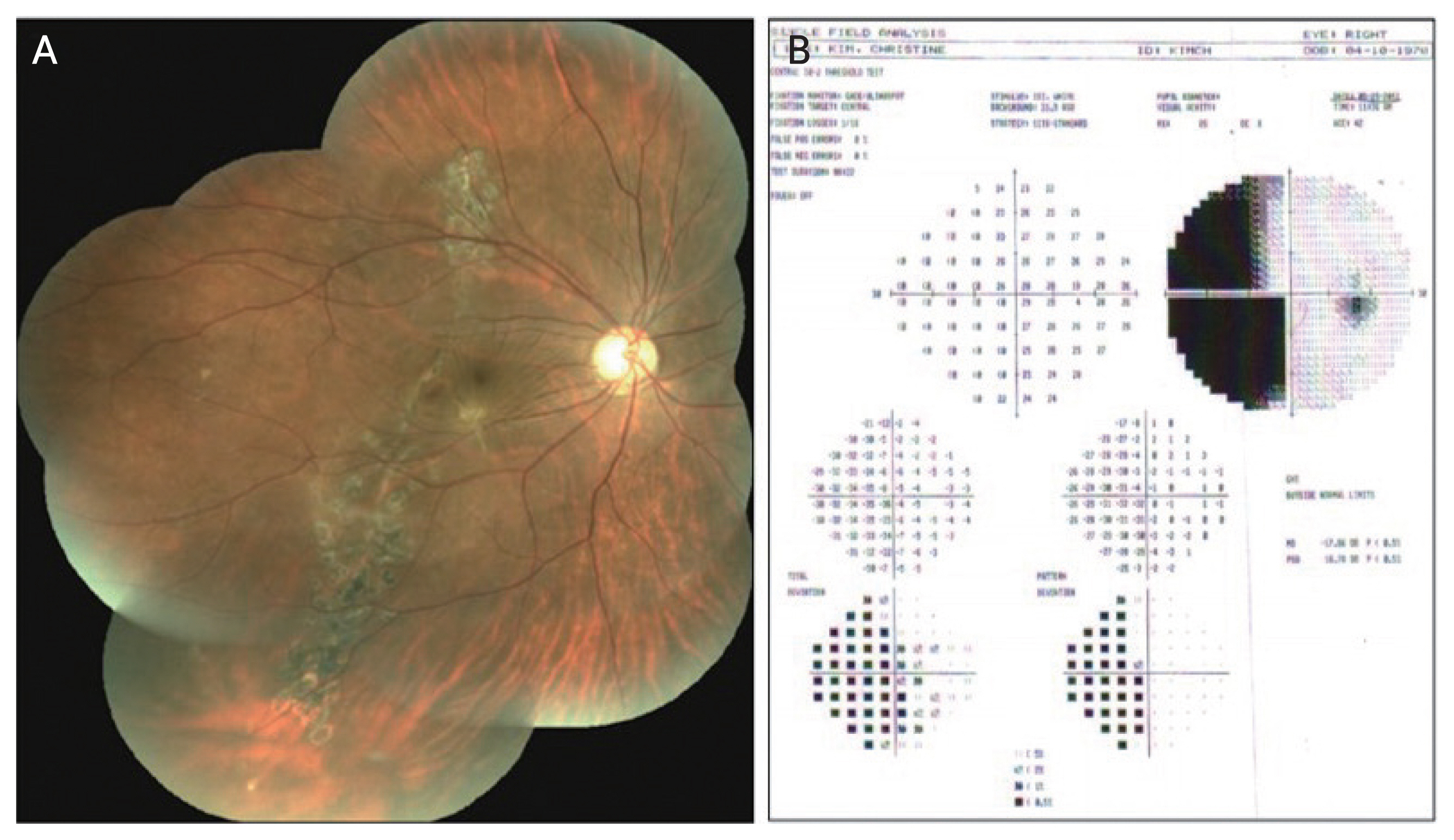

A total of 14 case reports (15 eyes of 14 patients) of adverse events associated with periocular acupuncture were identified between 1982 and 2020 (Table 2) [10–22]. The mean age of the patients was 52.71 ± 15.04 years. Of these patients, six (43%) were men and eight (57%) were women. The most common reasons for acupuncture were glaucoma (n = 4), blepharospasm (n = 2), and chronic conjunctivitis (n = 2). Additionally, there were cases of traumatic mydriasis (n = 1), ptosis (n = 1), lateral rectus palsy (n = 1), hemifacial spasm (n = 1), cerebral infarction (n = 1), and headache (n = 1). Practitioners were identified as licensed acupuncturists (n = 6), health workers (n = 2), and unlicensed acupuncturists (n = 3). In three cases, there was no mention of the practitioner.

Penetrating eyeball injuries, which were defined as injuries with at least one (entrance or exit) identified wound of the eyeball caused by acupuncture needles, were observed in 12 of the 15 eyes. Of the remaining three, one sustained a hematoma due to medial palpebral artery trauma, the other had optic atrophy due to pressure caused by the retrobulbar hemorrhage, and the last one had blepharospasm due to orbicularis oculi muscle tremor. Perforation injuries, defined as injuries with both entrance and exit wounds of the eyeball caused by acupuncture needles, were observed in 10 of the 12 total penetrating injuries. The remaining two without ocular perforation were cases of traumatic cataracts.

Case reports

1) Case 6

Fielden et al. [14] reported a case of a 67-year-old man with decreased visual acuity (VA) and pain in the right eye after periocular acupuncture for glaucoma treatment. He developed a retinal tear and hemorrhage in his right eye. There were two full-thickness retinal holes along the superior arcade with a vertical retinal laceration extending into the fovea. A 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) with endolaser photocoagulation and air-fluid gas (C3F8) exchange was performed. The VA in the right eye improved from 20/50 to 20/40 after surgery. The type of practitioner and exact acupuncture points were not specified in the report.

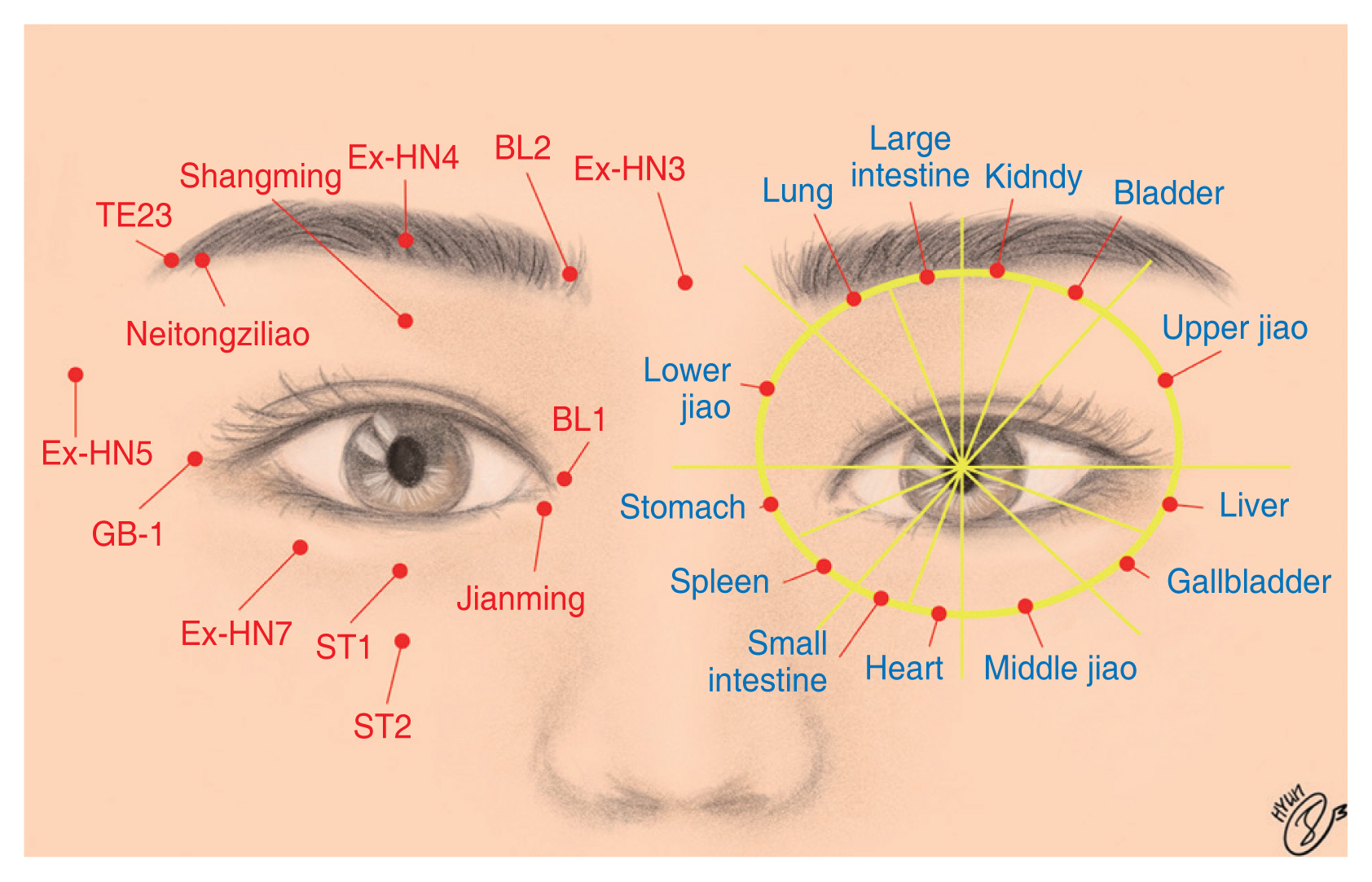

2) Cases 7 and 10

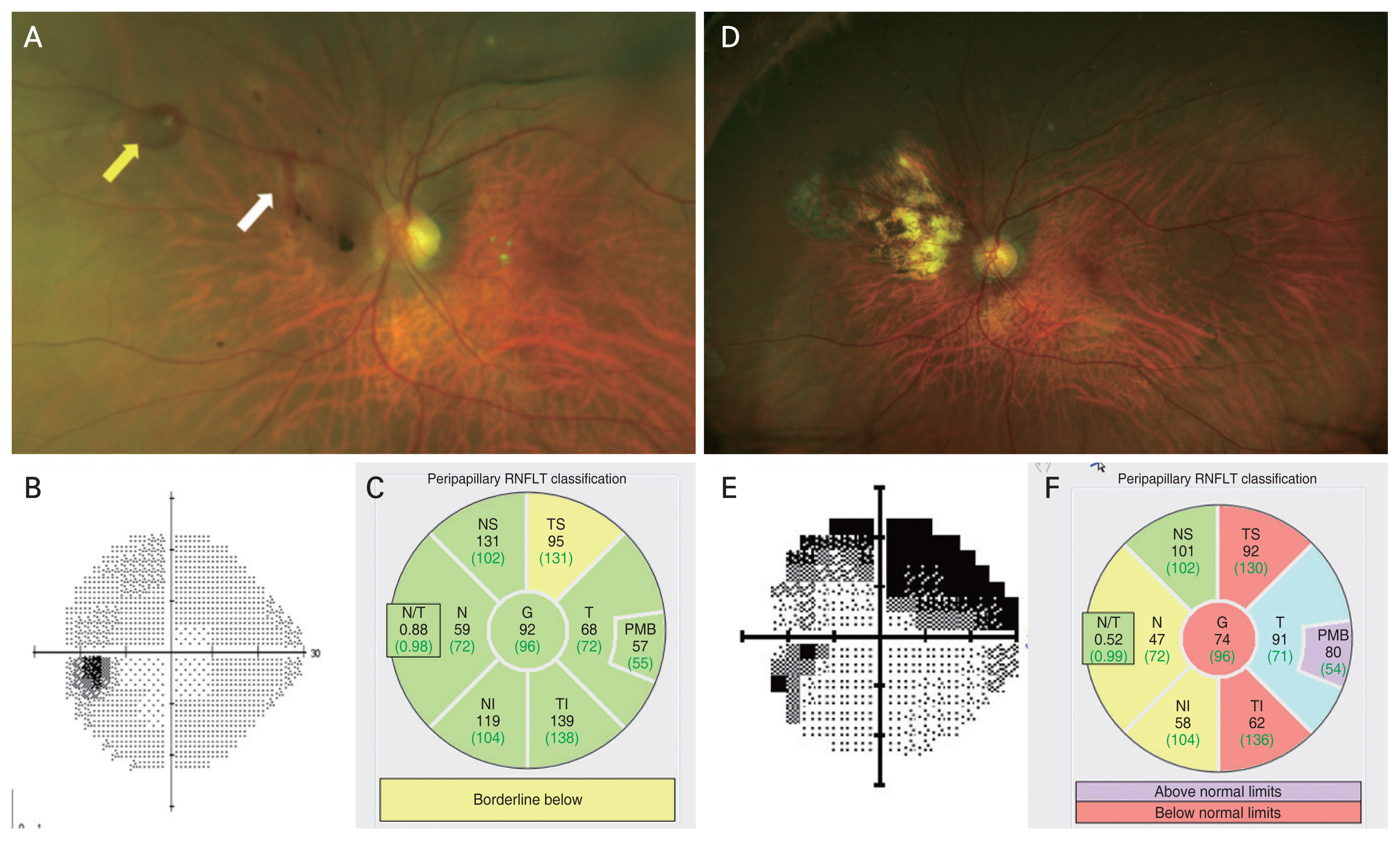

In 2013, Kang et al. [15] reported the case of a 42-year-old woman who presented with decreased VA and pain in her right eye after periocular acupuncture therapy for blepharospasm performed by an unlicensed acupuncturist. She had a vitreous hemorrhage and a linear retinal tear in the posterior pole, sparing the macula. Endolaser photocoagulation was performed around the lesion. An epiretinal membrane developed, and a visual field defect corresponding to the injury site was demonstrated using the Humphrey visual field test (Fig. 2A, 2B) [15]. The nasal hemianopsia remained unchanged, although a 25-gauge PPV with epiretinal membrane removal was performed.

Case 7. (A) Fundus photography before surgery for epiretinal membrane removal. This shows the distortion of blood vessels, marked retinal wrinkling, and striae with epiretinal membrane. (B) Humphrey automated perimetry shows atypical nasal hemianopsia of the right eye. Reprinted from Kang et al. [15], available under the Creative Commons License.

In 2016, we reported the case of a 62-year-old man who presented with acute ocular pain and decreased vision in his left eye [18]. He had undergone ocular acupuncture therapy by an acupuncturist 1 day earlier for glaucoma and chronic conjunctivitis. Eyeball perforation occurred, and intraocular inflammation, retinal hemorrhage, and vitreous hemorrhage were observed. An emergent 23-gauge PPV was performed. Although the causative organism was not identified, endophthalmitis was suspected, and an intravitreal antibiotic injection was administered during surgery. At the 3-month postoperative follow-up, the VA of the patient improved to 20/20. After 6 years of follow-up observations, the VA was maintained at 20/20; however, the visual field defect worsened (Fig. 3A–3F) [18].

Case 10. (A) The left eye, 1 day after injury. Retinal hemorrhages are observed in the superonasal quadrant of the retina (arrows), as well as vitreous hemorrhages and opacities. (B,C) On visual field examination, mild impairment due to glaucoma is noted. Peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness (RNFLT) was automatically measured at six sectors: temporal superior (TS), temporal (T), temporal inferior (TI), nasal inferior (NI), nasal (N), and nasal superior (NS). Global (G) RNFLT was obtained by averaging 360° peripapillary RNFLT measurements. (D) Six years after the acupuncture injury, an atrophic scar is observed in the fundus. (E,F) Progressive visual field impairment is observed with a decrease in peripapillary retinal nerve fiber thickness on optical coherence tomography. PMB = papillomacular bundle. Adapted from Chung et al. [18], available under the Creative Commons License.

3) Case 12

In 2018, Lee et al. [20] reported a case of traumatic optic neuropathy with eyeball perforation following acupuncture performed by an acupuncturist. A 63-year-old woman presented with a sudden vision loss in the right eye after acupuncture therapy for glaucoma. She had eyeball perforation with vitreous hemorrhage. Traumatic optic neuropathy was suspected based on the findings of a marked relative afferent pupillary defect and localized hemorrhage over the right optic disc. No systemic steroids for possible traumatic optic neuropathy were administered because of late presentation, and the patient was followed up without surgery. Her VA worsened from 20/20 to 20/600 and did not improve despite retinal hemorrhage resolution.

4) Case 13

In 2020, Denstedt et al. [21] reported a case of retinal detachment and posttraumatic proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) caused by a penetrating scleral injury with an acupuncture needle. A 49-year-old woman presented with severe pain after acupuncture therapy for headaches. She had eyeball perforation with intraocular inflammation, vitreous hemorrhage, and subretinal hemorrhage. This patient was managed with multiple vitrectomies and adjunctive intravitreal methotrexate for progressive PVR. Her VA improved from light perception to 20/40. The acupuncture practitioner was not specified in the report.

5) Case 14

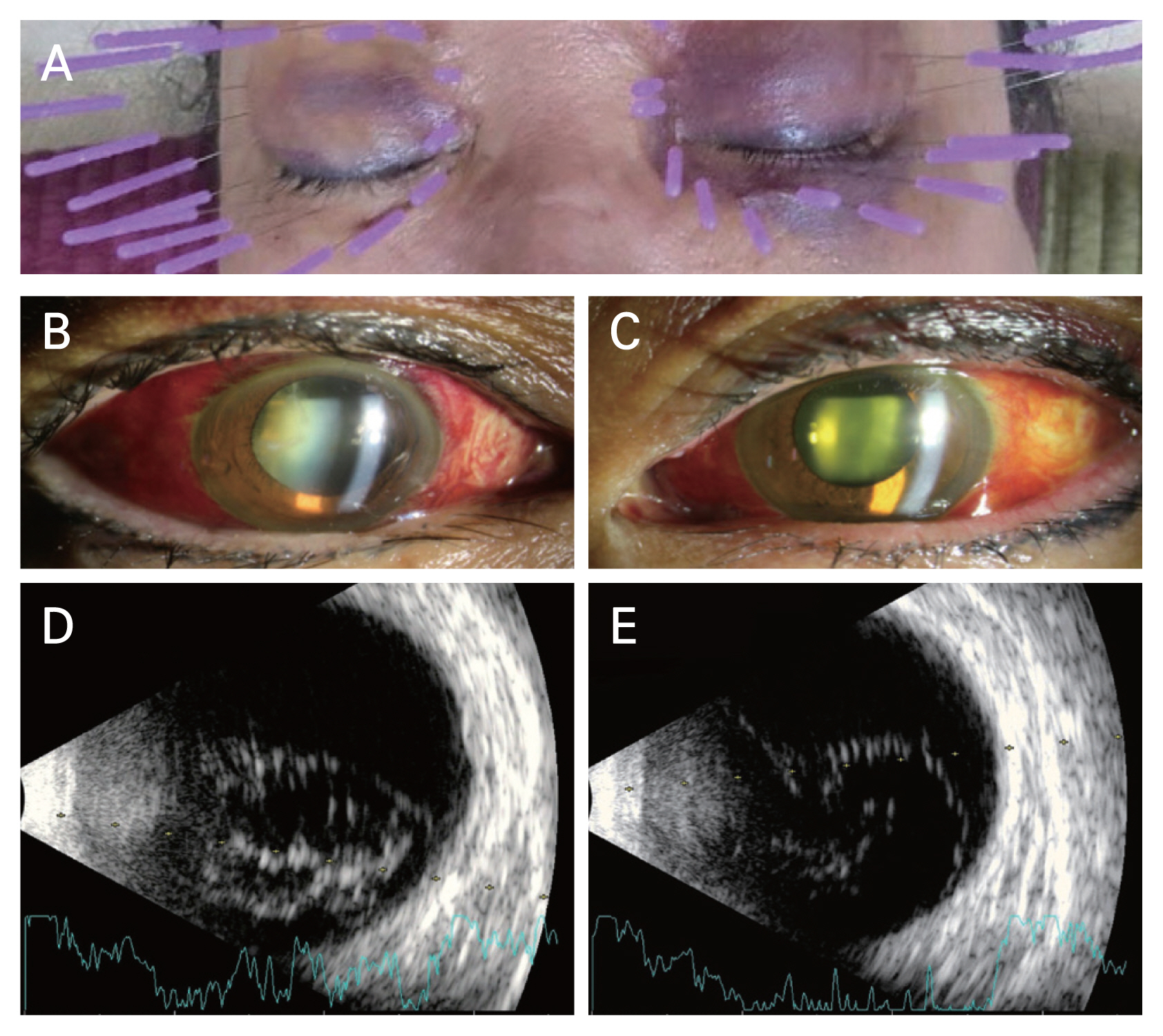

In 2020, Lee et al. [22] reported the case of a 58-year-old woman who presented with ocular pain and decreased VA in both eyes after acupuncture therapy performed by an unlicensed acupuncturist for glaucoma and cataract prevention (Fig. 4A–4E). She had bilateral vitreous hemorrhage with VA of counting fingers. Initially, emergency surgery for both eyes was planned, but the patient wished to undergo surgery in one eye only. Therefore, 23-gauge PPV was performed only on the right eye. Eyeball perforation with retinal tears was observed, and endophthalmitis was diagnosed in both eyes, although the culture results were not reported. The VA improved to 20/40 in the right eye and remained 20/2,000 in the left eye, without any further improvement.

Case 14. (A) The photograph is taken during the second periocular acupuncture procedure. Multiple bruises around both the eyes resulting from the first therapy are seen. (B–E) Slit-lamp photograph and B-scan ultrasonography of the patient at the first visit. Subconjunctival hemorrhage is observed in both the eyes. B-scan ultrasonography shows increased echogenicity implying vitreous hemorrhage in both eyes. Adapted from Lee et al. [22], available under the Creative Commons License.

Managements and Discussion

Although eyeball perforations are known to be mainly caused by trauma, they may also occur as a complication of retrobulbar anesthesia for intraocular surgery, such as cataract surgery and trabeculectomy [43,44]. Perforations are usually managed by PPV. In cases where retinal damage is not severe, treatment with endolaser alone has been reported [16,19]. However, in cases of perforation injuries caused by nonaseptic manipulation, such as periocular acupuncture, PPV was mainly performed [12,14–16,18,21,22]. In our review of cases, PPV was performed in six of 10 eyes with eyeball perforation. Vitreous hemorrhage was the most common cause of vitrectomy, and retinal detachment was observed in one case.

In the case of ocular acupuncture injury, it is thought that by removing vitreous hemorrhage and inflammatory products through PPV, ophthalmic fibrous proliferation is reduced to make the retina more stable, and bacterial endotoxins are removed as much as possible, thereby reducing the possibility of bacterial endophthalmitis [45–47]. In the case of patient 11, Lee et al. [22] considered the possibility that bacterial endophthalmitis occurred in both eyes after acupuncture injury. The patient underwent vitrectomy of only the right eye. Although PPV was not performed in the left eye, pain and VA improved after laser photocoagulation and intravenous administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics. However, the visual prognosis of the left eye was worse than that of the right eye. Since acupuncture-induced ocular perforation may not be caused by aseptic manipulation [18], early treatment should be actively considered through vitrectomy to remove vitreous hemorrhage, inflammatory products, and bacterial toxins.

Acupuncture around the periorbital region poses a risk of perforation and infection, especially if performed by an unqualified individual [15,22]. At least three of the 15 cases in our review were procedures performed in unlicensed acupuncture centers. Of note, permanent vision loss can arise from acupuncture. Therefore, acupuncturists should get familiar with the eye anatomy of acupoints and avoid blood vessels or nerves during needle manipulation and avoid manipulation methods, such as thrusting or vigorous lifting, when acupuncturing intraorbital acupoints [48]. Similar to acupuncture, intravitreal injection is also performed to treat eye diseases, such as neovascular age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and retinal vein occlusion [49,50]. There is also a risk of infection in the case of intravitreal injection for therapeutic purposes. Therefore, it should be performed under aseptic conditions after administering betadine to the eye. The injection needle penetrates only through the plane of the ciliary body. This is because the flat part of the ciliary body is a narrow area of approximately 4 mm, and when the puncture point is out of that range, ciliary body and retinal hemorrhage, as well as retinal tear and detachment, may occur [18,51]. Acupuncture performed without recognizing the importance of aseptic manipulation may pose a risk of endophthalmitis, vitreous hemorrhage, and retinal tear. In the case of patients 7 and 11 [18,22], endophthalmitis was presumed to have occurred based on pain, intraocular inflammation, and vitreous opacity. The risk of endophthalmitis, vitreous hemorrhage, and retinal laceration is higher when nonsterile techniques are adopted by unlicensed acupuncturists. Therefore, aseptic acupuncture should be performed by licensed acupuncturists. Adequate training of modern acupuncturists, particularly emphasizing the study of sterile needle techniques and knowledge of human eye anatomy, is important and is required to prevent periocular adverse events. Since modern acupuncture, which is currently being practiced in several countries, emphasizes knowledge of eye anatomy and aseptic acupuncture, it is supposedly less likely to cause periocular adverse events.

Periocular acupuncture is being performed worldwide for many ophthalmologic and nonophthalmologic conditions, such as headache, trigeminal neuralgia, neck stiffness, and acute lumbar sprain [17,26]. The incidence of complications, including perforation, is likely to increase as the acupuncture site is in close contact with the orbital margin. Additionally, vision loss may occur because of ocular perforation. Therefore, care should be taken during acupuncture, the patients should be closely monitored after the procedure, and any possible future complications should be noted. All these acupuncture points are anatomically predisposed to optic nerve injury and globe perforation owning to the proximity of the eyeball structures. Therefore, the acupuncturist should recognize and distinguish between the pain caused by penetrating eyeball or optic nerve injury and the pain occurring as part of the therapeutic effect of the acupuncture. Many patients and practitioners mistakenly think that a stronger pain sensation will give rise to better outcomes [48], when in fact, they cause severe adverse events, such as eyeball perforation. It may equally be important to have a good understanding of the ocular anatomy to avoid potential complications.

In our review, no specific periocular area was identified as more prone to eyeball injury. A direct link between the acupuncture site and penetrating injury was not observed. As shown in Table 2 [10–22], only three cases (cases 8, 11, and 12) reported specific acupuncture sites out of 12 eyes with penetrating injury, and the acupuncture sites were ST1, Ex-HN4, and GB1, respectively. Therefore, ocular damage could be induced at various periocular sites, but the relationship between specific sites and injury could not be analyzed because of the small number of cases.

Conclusion

Acupuncture therapy around the eye is a risky procedure, with no robust evidence of its benefits. Hence, it is important to have a good understanding of eye anatomy to avoid potentially blinding complications. Additionally, it is necessary to strictly monitor the patient’s condition after the procedure, and any complications and associated symptoms that may occur in the future should be explained to the patient in detail.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Chehyun Lee for the illustration design.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

Funding: None.