Keratoconus is a non-inflammatory disease of the eye [

1] that causes protrusion of the central cornea, progressive corneal thinning, and decreased visual acuity due to irregular astigmatism. Patients with mild keratoconus usually have their vision corrected with eye glasses. If correction is difficult contact lenses or surgical treatment for the improvement of vision are considered. Surgical treatments typically include corneal collagen cross-linking [

2], corneal ring implantation in the stroma [

3], and corneal transplantation [

4]. These treatments are invasive, however, thereby creating burdens for patients that elect to undergo surgical correction. Corrective contact lens wear is relatively more popular than surgical treatment, and as it turns out, contact lenses may be an effective first treatment modality for mild keratoconus patients. In the past, the proportion of keratoconus patients treated with contact lenses was low due to difficulty in domestic accessibility. Currently, an increasing assortment of available contact lenses has expanded the use of corrective contact lenses for the treatment of keratoconus patients. Despite this increase in the prescription of corrective contact lenses for treatment of keratoconus patients, existing studies have focused mostly on the clinical results of contact lens use, such as changes in refractive error, corneal topography, and corrected vision. In contrast, studies focusing on vision quality, quality of life, social status, and psychological satisfaction in patients using contact lenses have been rare. Although visual acuity is well corrected in most patients using contact lenses, this does not necessarily indicate that there is an improvement in the quality of vision and patient satisfaction, which includes factors such as difficulty with driving at night, blurry vision, halo phenomena, and discomfort.

Materials and Methods

Study subjects

This study was conducted at Gangnam Severance Hospital, Seoul, Korea, and Ye-dream Hospital, Seoul, Korea. We analyzed the changes in visual function, visual symptoms, social role function, and psychological well-being experienced by patients following their use of contact lenses for the treatment of myopia and keratoconus. Only subjects with corrected vision over 0.8 measured by the Snellen chart were included, and were surveyed by questionnaires prior to using contact lenses and three months following the use of contact lens.

Only patients that could endure contact lens wear every day for over 6 hours per day were selected. Patients with specific reasons to not regularly wear contact lenses were excluded from the study. After examination of the anterior segment, patients with chronic corneal erosion, corneal dystrophy, severe allergic conjunctivitis, or various eye diseases were excluded. Patients with severe discomfort or pain at the initial visit, or patients expressing significant levels of fear during the contact lens trial test were also excluded. In participating patients, the patient eye with a more severe degree of keratoconus or myopia was selected for the study. Thinsite (Art Optical, Grand Rapids, MI, USA) lenses were prescribed to myopia patients and Achievement (Art Optical) lenses were prescribed to keratoconus patients.

Methods

The patients in this study were informed about the advantages and disadvantages of contact lens treatment and were notified that, apart from the survey, there would be no additional fees or examinations due to their participation. The questionnaires were prepared based on the Myopia-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire and modified for contact lens-treated patients in this study [

6]. Originally designed to evaluate the quality of life associated with myopia and vision, the Myopia-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire contains 51 items from the NEI-VFQ (National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire) developed by the National Eye Institute together with 14 items from the Vision Function-14 index developed by Steinberg [

7,

8,

9]. The content of the questionnaire was separated into four areas of visual function, visual symptoms, social role function, and psychological well-being. The questionnaire's Cronbach's ╬▒ for reliability and validity have been analyzed in previous studies, and both values had excellent ratings [

10]. The survey consisted of 42 questions (14 questions about visual function, 12 questions about visual symptoms, five questions regarding the social roles of participants, and 11 questions on the psychological status of participants), and each item was measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale. Higher scores indicated greater satisfaction. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Gangnam Severance Hospital (3-2016-0195), and was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

We used statistical software IBM SPSS ver. 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to calculate statistically significant differences between the two groups, and the Wilcoxon signedrank test was used to compare the groups of patients before and after the wearing of corrective contact lenses.

Results

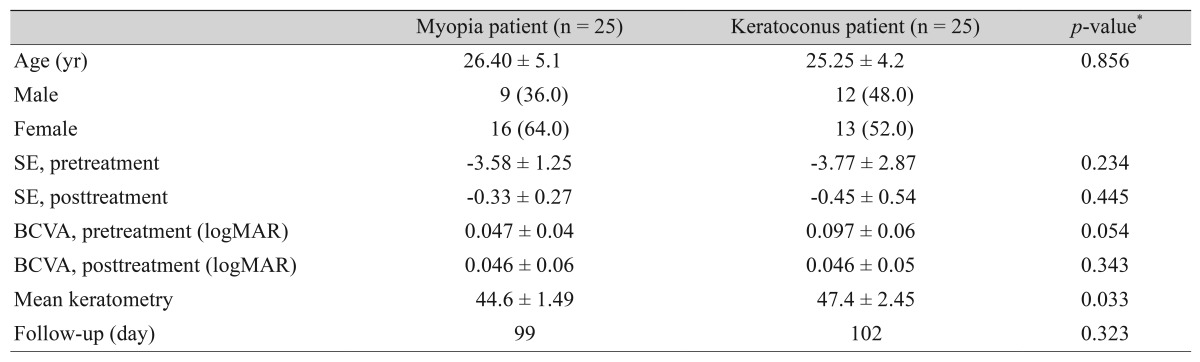

Among 50 enrolled patients, 25 were myopic and 25 had keratoconus. The vision of all patients had been corrected with glasses prior to treatment with contact lenses. Between the two groups, there were no statistically significant differences in corrected vision or refractive error before and after contact lens usage, including during the follow-up period (

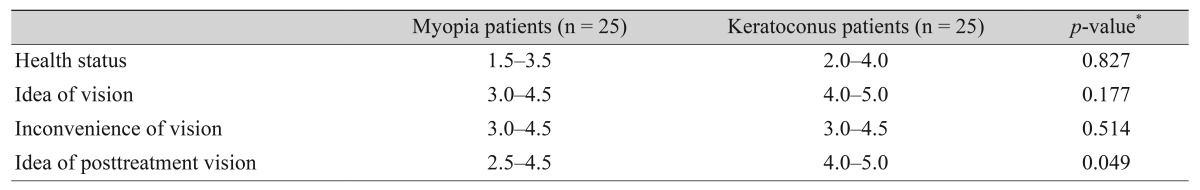

Table 1). Both patient groups reported no significant differences in how they thought about their current health status, vision, and levels of discomfort. Keratoconus patients, however, had lower expectations for good visual acuity compared to myopic patients (Mann-Whitney

U-test,

p = 0.049) (

Table 2).

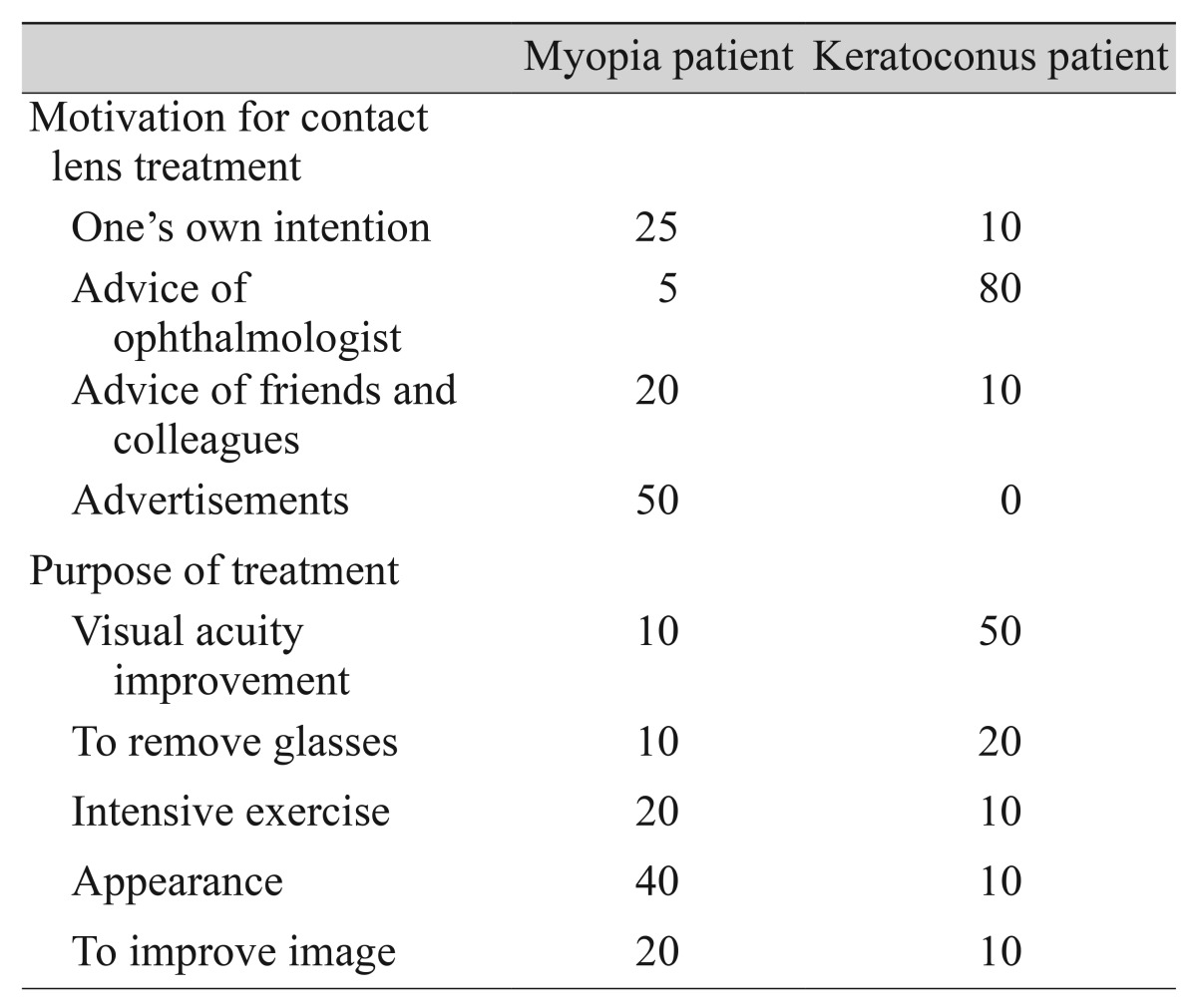

Improvement in appearance accounted for the largest proportion of patients seeking treatment for myopia (40%), whereas visual acuity improvement (50%) accounted for the largest proportion of patients seeking treatment for keratoconus (

Table 3). In myopic patients, advertisements provided the greatest motivation for starting treatment with corrective contact lenses (50%), but in keratoconus patients, advertisements had no motivational effect. Instead, the recommendation of doctors (80%) was the major motivation to begin contact lens treatment in patients with keratoconus (

Table 3).

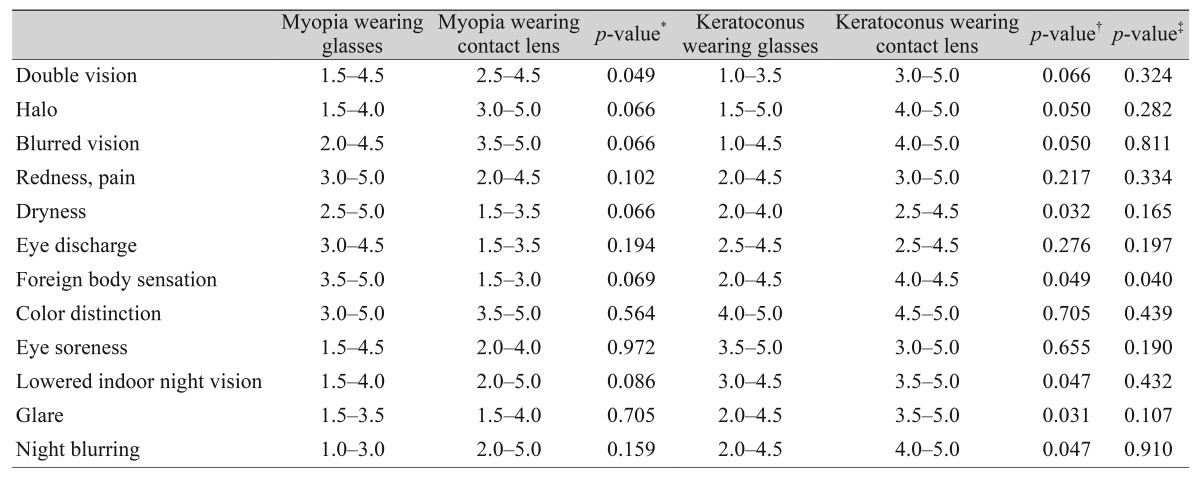

According to the survey, in terms of the comparison of various aspects before and after the wearing of contact lenses, usage of corrective contact lenses by myopic patients significantly improved double vision (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.049). On the other hand, keratoconus patients experienced improvement in halo phenomena (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.050), blurred vision (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.050), lowered indoor night vision (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.047), glare (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.032), and night blurring (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.047) (

Table 4). Myopic patients did not experience significant changes in discomfort due to the wearing of contact lenses. Keratoconus patients felt improvement in symptoms of dryness (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.032), but experienced worsened foreign body sensation (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.049). Comparison of symptom changes post-lens wear between the two groups revealed that only foreign body sensation was statistically different between the two groups (Mann-Whitney

U-test,

p = 0.040) (

Table 4).

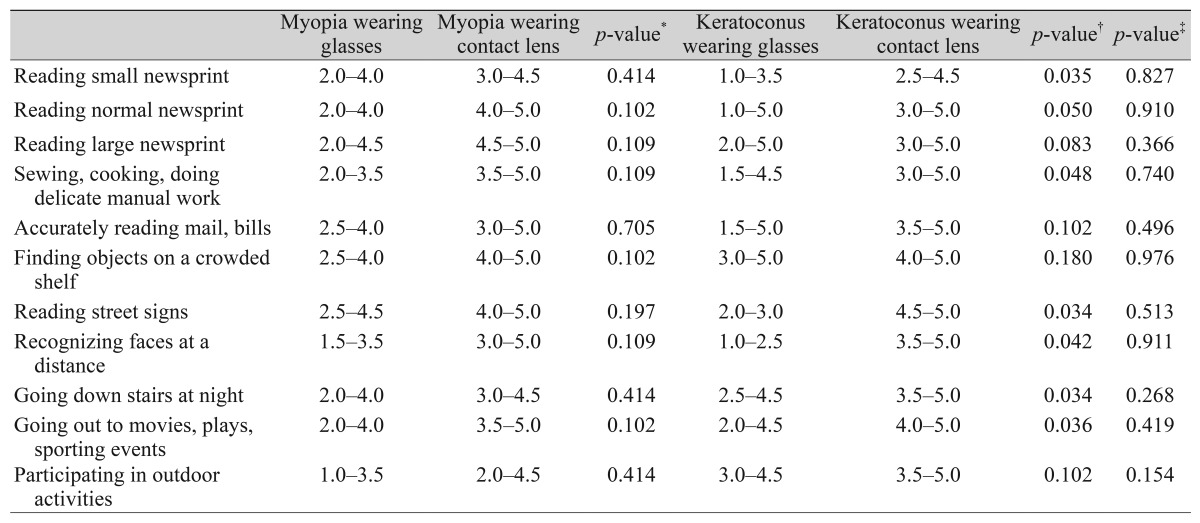

Comparison of subjective visual function in the daily activities of patients in both groups before and after the wearing of contact lenses revealed that keratoconus patients experienced improvement in reading small newsprint (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.035), doing delicate manual work (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.048), reading street signs (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.034), recognizing faces at a distance (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.042), and going down stairs at night (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.034). Myopia patients did not experience significant changes in any area of visual function following the wearing of contact lenses (

Table 5).

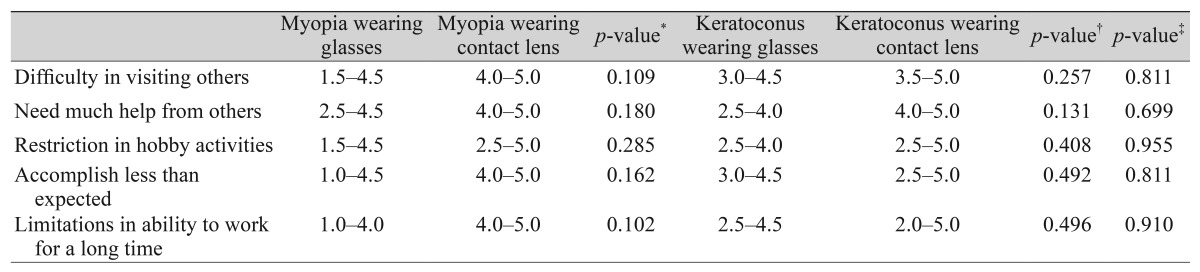

Both myopic and keratoconus patients reported no significant differences on variables quantifying their social roles prior to and following the wearing of contact lenses (

Table 6).

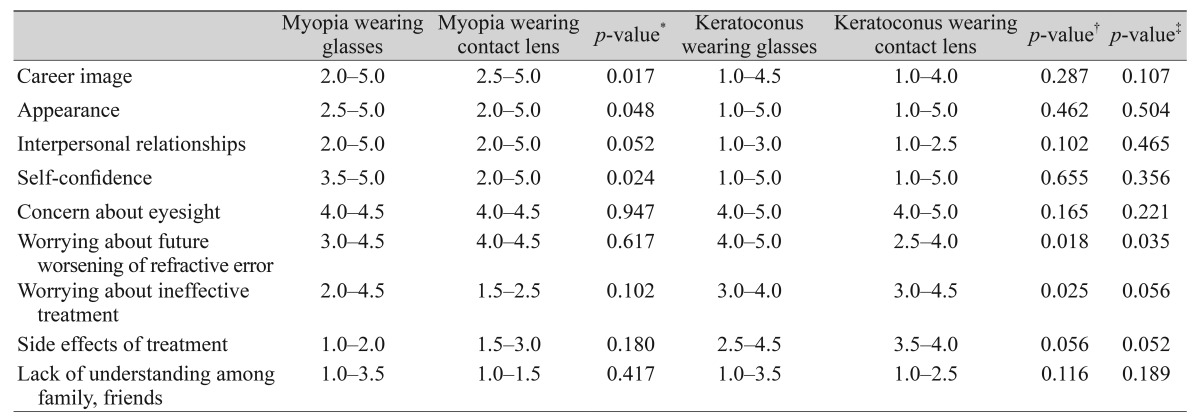

Items measuring the psychological well-being and mental condition of the patients showed myopic patients reported improvement in satisfaction with their appearance (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.048), career image (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.017), and self-confidence (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.024) following the wearing of contact lenses. In contrast, keratoconus patients did not experience the same results (

Table 7). Following the wearing of contact lenses, keratoconus patients felt greater anxiety regarding the potential future worsening of refractive error (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.018) and ineffective treatment (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.025) in comparison to their levels of anxiety about these outcomes before treatment (

Table 7).

Discussion

In previous research, Kymes et al. [

11] explained that keratoconus disease rarely results in blindness, but because the disease affects young adults, the magnitude of its public health impact is significant. In addition, Erdurmus et al. [

12] found that subjects with keratoconus who wear RGP, hybrid, or soft toric contact lenses reported similar impacts on their quality of life due to the wearing of contact lenses as the patient findings reported herein. As in these previous studies, our study found that even though the visual acuity of keratoconus patients was well corrected by glasses, their level of discomfort with glasses was not inconsequential, which in fact had a great impact on their lives. Moreover, the discomfort caused by the wearing of glasses in keratoconus patients could be resolved by treatment with contact lenses. Our study began with the underlying assumption that changes in visual quality, psychological status, and levels of satisfaction due to the wearing of corrective contact lenses might impact myopic and keratoconus patients differently. In this study, keratoconus patients experienced significant improvement in more areas than myopic patients. This might imply that the mean satisfaction of visual quality in keratoconus patients was lower than that in myopic patients before treatment (

Table 4,

5,

6). In the baseline survey, in comparison to myopic patients, keratoconus patients also had lower expectations for improved visual acuity following contact lens treatment. What is more, despite overall improvement in visual function and visual symptoms, keratoconus patients continued to worry following treatment that the treatment would have no effect (

p = 0.025) (

Table 7). This might be due to lower confidence in corrective lens treatment in keratoconus patients, anxiety about the lessening of treatment effects over time, and low satisfaction caused by poor vision quality (even with corrected visual acuity due to glasses) prior to contact lens use.

It is interesting to note that, as revealed in participant surveys, subjective improvement in visual symptoms and function was experienced at different distinct points. Regardless of font size, myopic patients did not experience any improvement in reading. However, keratoconus patients felt better in reading small print with the use of contact lenses (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.035), which may imply that these patients normally feel a sense of discomfort in near vision, especially with small print (

Table 5). The results above correlate with the fact that keratoconus patients experienced significant symptom improvement in doing delicate manual work (

p = 0.048). In light of these results, in comparison to myopia patients, the use of corrective contact lenses by keratoconus patients broadens their spectrum of activities. This broadening of activities leads to the improvement of vision quality and quality of life.

Furthermore, myopic patients did not experience improvement in low-light activities (e.g., lowered indoor night vision, glare, night blurring, or going down stairs at night), whereas keratoconus patients experienced significant improvement in these activities (

p = 0.047, 0.031, 0.047, 0.034, respectively) (

Table 4,

5). Thus, in the case of keratoconus patients, corrective contact lenses might decrease discomfort and increase vision quality in low-light settings better than eyeglasses. This may be because eyeglasses cannot revise corneal astigmatism as well as contact lenses can, resulting in lowered contrast sensitivity and severe discomfort in the dark [

13].

Opposite to our expectation, the use of corrective contact lenses decreased dry eye symptoms in keratoconus patients. This might be due to increased corneal sensitivity and prolongation of tear break-up time caused by the covering of tears with contact lenses [

14]. Keratoconus patients experienced greater foreign body sensation in comparison to foreign body sensation before the use of contact lenses (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p = 0.049) and in comparison to myopic patients using contact lenses (Mann-Whitney

U-test,

p = 0.040). This is likely due to various reasons, such as friction between the corneal protuberance and the contact lens and increased corneal astigmatism, which may cause greater lens decentration and movement.

In terms of social role functions of patients, both myopic and keratoconus patients' satisfaction increased following contact lens usage, but the difference was not statistically significant (

Table 6). This may be because the selected patients had corrected visual acuity over 0.8, and thus may not have experienced significant disturbances in their social lives before the wearing of contact lenses.

Motivation for treatment with contact lenses and the purpose of treatment are also different in keratoconus and myopia patients. Although appearance accounted for the majority of patients' treatment purpose for patients with myopia, for keratoconus patients, visual acuity improvement accounted for the largest proportion of treatment purpose. These trends seem related to contact lens treatment motivation. Most myopic patients were persuaded to use contact lenses via exposure to advertisements, which tend to appeal to appearance and image, whereas the advice of ophthalmologists had little effect on the motivations of myopic patients (

Table 3). According to these results, doctors need to encourage patients to start contact lens treatment based on the purposes and motivations for treatment that are specific to the disease group, emphasizing the improvement of self-image for myopic patients and emphasizing visual acuity improvement for keratoconus patients.

In survey items quantifying psychological well-being (

Table 7), myopic patients showed increased satisfaction in beauty-related items (e.g., career image, appearance, self-confidence), while keratoconus patients did not show statistical differences in these areas. This can be interpreted in view of the results in

Table 3, which demonstrate that the motivation and purpose of treatment for most keratoconus patients was for visual acuity improvement, but not for appearance and image.

In conclusion, although the same contact lens treatment is applied, different groups of patients are motivated by different factors, and may experience different types of discomfort and improvement depending on the type of disease. Thus, ophthalmologists need to account for the type of disease and must consider not only corrected vision, but also subjective changes in overall vision quality, satisfaction, and psychological status among different patients. Based on the specific findings herein, contact lens treatment can be the first treatment modality for keratoconus patients.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print